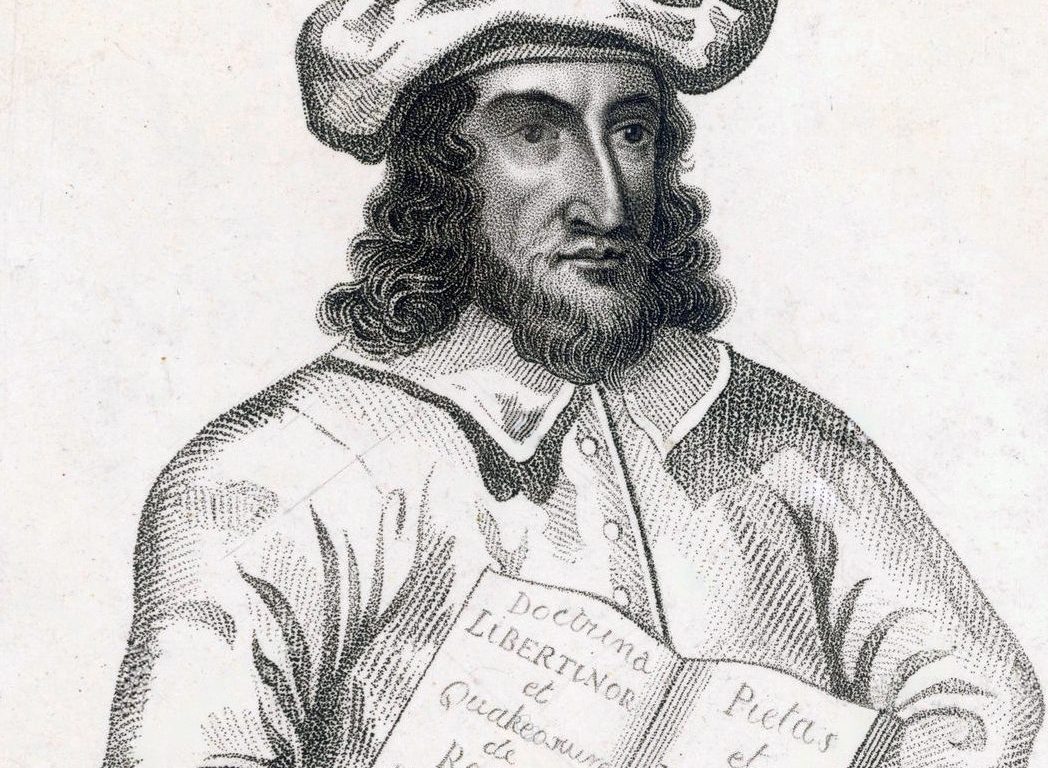

We wrote earlier about Thomas More, The Man for All Seasons, and famous for standing by his principles against Henry VIII to the point of being beheaded in 1535. In the 17th century the revolutionary John Cooke met a similar end: he was hung, drawn and quartered in 1660 by Charles II as a regicide for acting as Charles I’s prosecutor. Both saw and acted on the need for timely justice. Geoffrey Robertson in The Tyrannicide Brief makes a spirited argument that Cooke sought to hold Charles I accountable for what we would now characterize as war crimes or crimes against humanity. Of interest to us here was his work as a Judge in Ireland under Cromwell’s Protectorate.

Time and again, when given the opportunity to start or refresh a legal system there is nearly universal recognition that timeliness is fundamental to justice. Cooke was appointed a Judge in Ireland during Cromwell’s Protectorate. Despite the generally oppressive conduct of Cromwell’s Irish occupation, Cooke’s court was based on his own legal catechism that rings of Job 28:

“If I did not minister speedy justice to the poor for the love of justice and to the rich for a small fee when I sat in open court so that every man might see and hear the reasons for my proceedings… let my arm be broken by the hangman and heaven curse my lands…”

John Cooke suffered the effects of ineffective justice in many respects. He had relatives imprisoned for debt, and suffered long delays in cases resulting in the death of a member of his family. He was keenly aware of the flaws of the 17th century’s British Courts and was a thoughtful, determined and far-sighted reformer. He advocated pro bono legal services, the consolidation of the patchwork quilt of courts and other reforms centuries ahead of his age.

In Ireland he thought he had a blank canvas on which he hoped to make a good, just, and Godly impression. The universalism of his vision is evidenced by the fact that John Cooke, a Puritan, wanted to go to very Catholic Ireland to give speedy and fair justice to Catholics and Protestants alike.

In the practice before his court Cooke fixed the fees of the lawyers. He did justice fairly and as speedily as possible without being peremptory. He didn’t milk his position—a common frailty then and in many ages and places. He believed his work in Ireland was the work of God that would pave the way for law reform in England. He heard cases as soon as possible as opposed to many other judges who fixed a distant date in order to take overlong vacations.

John Cooke’s work eventually came to nothing when Henry Cromwell, the hapless and weak younger son, helped close down the Munster court where Cooke operated. Cooke was appointed to be a judge of the new court that would replace it, the Upper Bench. Cooke was very discouraged and sent in his resignation, saying that “his conscience would not permit him to accept a position that was antipathetic to all he believed in and had struggled to achieve.”

This obscure chapter of legal history demonstrates that timeliness can be achieved within a system that is otherwise deeply flawed. It adds another example to the observation that historical periods of timeliness have generally flowed from individual, charismatic judicial leadership. Sadly, it also shows that timeliness is a fragile virtue that is often put aside when other aims take priority.

Enduring timeliness will depend on using novel tools to achieve ancient goals and embedding them in justice systems in ways that live beyond the service of the John Cookes of our age.